4 models of software development as a factory

Summary: Agile software development came from borrowing processes and ideas from manufacturing. Is software engineering like factory work? I examine four metaphors of software engineering as a factory.

Many of the processes we associate with the Agile movement--and many of its ideals--were inspired by manufacturing process management, namely Lean Manufacturing and the Toyota Production System. Many people criticize the Agile movement because software development is very different from manufacturing, so the metaphor might be more harmful than helpful.

Because they believe it is harmful, people have pulled back from the metaphor and only used what seems appropriate for teams of programmers. However, do those people know anything about what manufacturing, especially Lean Manufacturing, is like? How do they know that software engineering on a team is not like building a car?

I've been reading books on Agile and the Toyota Manufacturing Process to understand what's happening in my industry. My experience on development teams and talking to other developers is that only a few know anything about manufacturing. They only imagine that building a car must be like turning the same screw on 1,000 different cars every day. My research tells me it's anything but. And by doing that, they're acting like a dysfunctional factory. Maybe it's time to reexamine this bias.

In this essay, I'd like to dig deep into the metaphor. I'm asking the question: How *is* software development like a factory? I explore four different interpretations and their consequences.

1. Dev team as factory

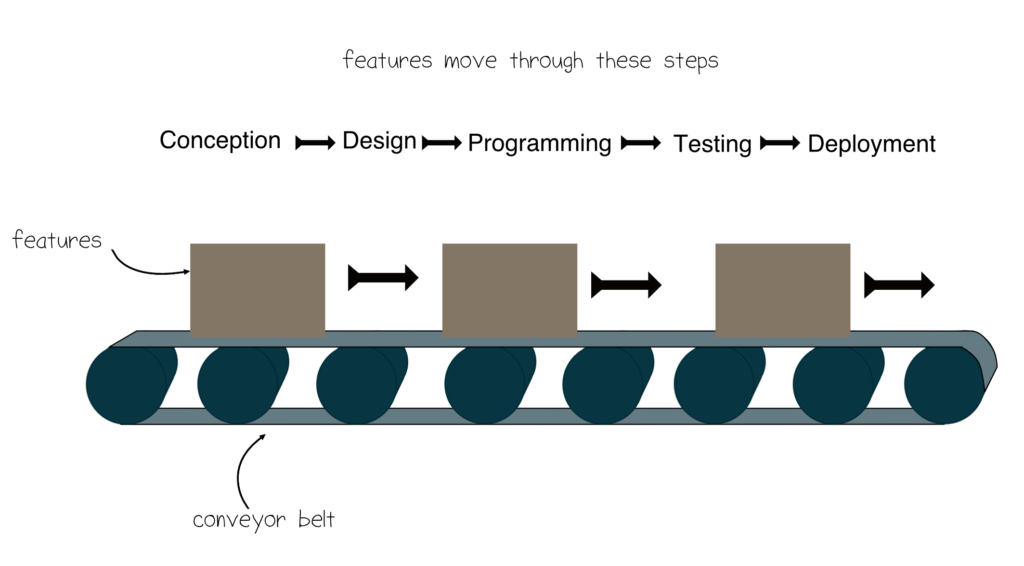

I think the most popular way to imagine a dev team as a factory is to see it as a set of features moving down an assembly line, getting gradually closer to deployment. The feature goes from conception to design to scheduling in the sprint to development, through code review, then testing, and finally deployment.

Ideally, the process always flows forward as people complete each step. This way of rationalizing the process is strangely soothing, especially to a manager who wants to track progress. The number of tickets deployed, or its proxy Velocity, feels like a convenient metric for how the features are coming along. However, we know velocity is flawed.

Fleshing it out

To flesh out the metaphor, the people working the process are like factory workers. Work comes to their station, and they do it. So, a feature gets to QA, QA tests the software and hits a button for it to proceed to the next step. Each worker is a cog in a larger machine, and no one has to know more than their job.

Consequences

What are the consequences of this model? From my experience, this model makes the developers, and probably the other folks on the "assembly line," feel like cogs in a machine. Everyone understands their part, but they can't appreciate the whole. They are like so many Lucille Balls desperately trying to keep up.

Management rewards workers for velocity. The devs don't know how each feature fits into the whole. All they know is that it was decided upstream from them, and if they pass it on, they can push that button. And so problems get pushed down the line. I've been there, and it's not fun.

The teams are divided by function. That means design, development, testing, and deployment are separate groups. Instead of working together, this metaphor can create animosity between the groups as they blame each other for problems.

2. Software as factory

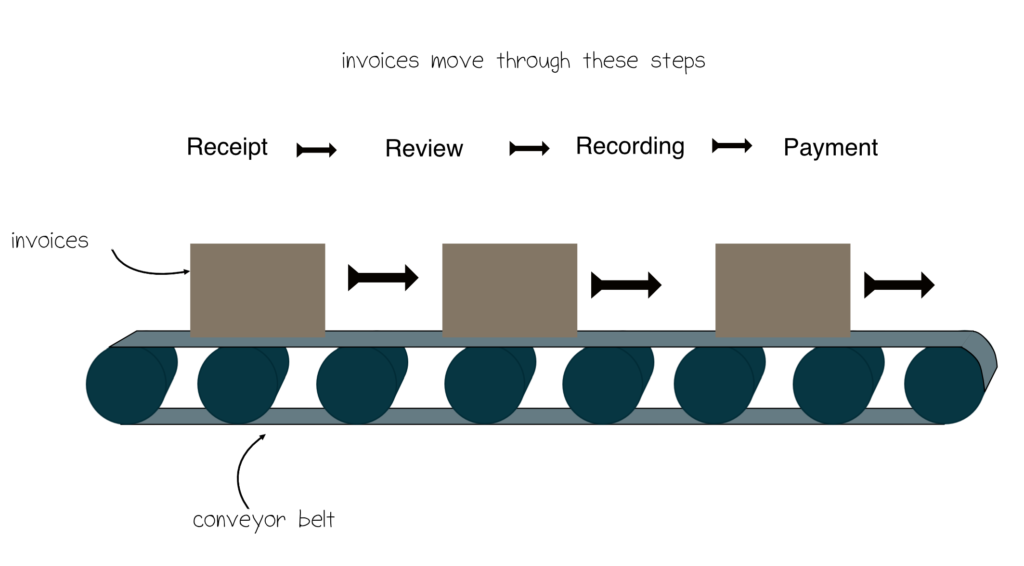

I have never seen this metaphor used, but I think it has some merit. Instead of seeing the team as a factory, you see the software as a factory. If car factories deliver cars, your accounting software delivers accounting. A smoothly running factory means smooth accounting. That means invoices move down an assembly line. Programmers build that assembly line.

Fleshing it out

If our software is the factory, how do we correspond the various roles? At the bottom, invoices and payments are the partially completed cars moving through the assembly line. As an invoice arrives, it moves through a series of steps, like review, recording, and payment.

The factory workers are the necessary humans in the accounting loop---usually the customers of the software, but occasionally, someone from the software company will have to unjam the works. They work at their stations and review invoices or sign checks.

So what are the programmers, designers, and operations people, then? They're the process engineers, of course. They are making the machinery that the factory workers use to do accounting.

Consequences

I like this model because it aligns everyone to the job the customer is paying for. Think about it. Toyota's process engineers ensure workers can safely and effectively deliver cars to customers. Wouldn't it be nice if everyone's job at an accounting software company was to ensure that accountants could effectively deliver accounting to their customers? It's much better than the job of providing accounting software features. Customers aren't paying for features. They want their accounting done.

This metaphor also means that every software engineer at the company has to understand accounting. I believe that programmers should become subject matter experts themselves. You can't engineer a process for building cars if you don't know about building cars. You can't engineer a process for accounting if you don't know about accounting.

Further, it means that the programmer, like the process engineer, sometimes goes into the factory to help clear things up. Likewise, you'll see programmers helping customers with accounting issues, like not knowing what to do with a particular invoice. If it's your job to deliver accounting, and your factory's current machines can't handle it, you've got to do it by hand.

Finally, this metaphor reunites teams. Programmers are not at different stations from designers. They're all there to make this factory run smoothly and improve the customer's work. What would an Agile team look like if they took this approach?

3. Compiler as factory

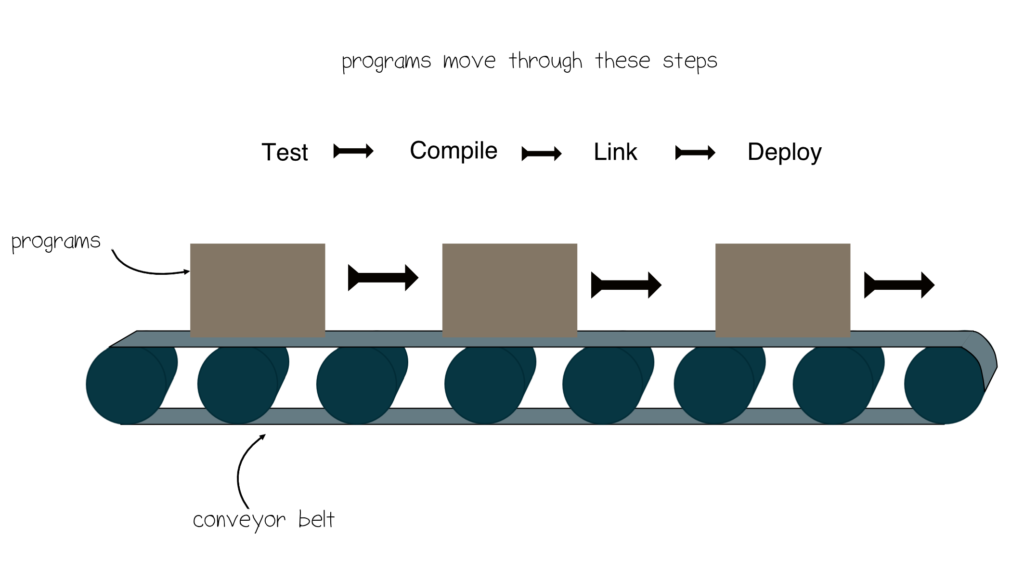

I want to explore the compiler as the factory. In this metaphor, the various software artifacts the team deploys are the product. The compiler, the build tool, etc., are the factory workers putting the thing together.

Glenn Vanderburg inspired this metaphor in a series of talks he has given.

Fleshing it out

Let's see how the various pieces correspond in this metaphor. The car, our product, is the artifact that runs the software. That could be a binary for a compiled language or a set of files that a runtime will interpret. The factory workers, and the whole factory, are the compiler and build tools that assemble that artifact. So, where do programmers fit in?

Well, the programmers are engineers. They design the artifact their compiler will build using high-level design documents that they call *programs*. That's right. Coding up a solution is a blueprint for the compiler to use to know what to build. Engineers do tests and experiments to make sure their designs work. And so do programmers!

Consequences

This metaphor boldly lets us call ourselves *engineers*. Watch the talk to understand how programmers typically caricature the idea of engineering. I like that we can be engineers again and not "developers."

The metaphor's main problem is where the other disciplines come in. Where does the designer fit? Are they industrial designers working alongside industrial engineers to design the product?

Another problem is how programmers get customer feedback about how to improve the software. I imagine programmers and designers in an R&D lab trying out different ideas and doing tests to see how well they work with real customers. In this way, they may be more like an IDEO product design team than manual laborers.

4. Brain as factory

I want to explore the brain as a factory. Arty Starr's excellent book Idea Flow inspired this metaphor. If we do a bottleneck analysis of software engineering work, the limited resource is time in the programmer's brain. If we flesh out the metaphor, then the place where all of the important work happens--the factory--is the brain. The product is commits to the software.

Fleshing it out

This metaphor may be the most challenging to flesh out. The brain is the factory, where the worker operates on the product. The worker is the programmer who can operate that brain. The inputs to the factory are the codebase and a desired change (a new feature, a bug fix, etc.). The output is a commit to the codebase.

Consequences

This metaphor is very similar to the first metaphor, where the team is the factory. However, this one highlights the importance of the programmer's ability to understand the code and the desired change. Anything that hinders those understandings will slow down the factory.

This metaphor breaks down because other stuff is involved, including the intra-team interactions, the tooling, and the codebase. Perhaps it would be better to adopt the first metaphor (dev team as factory) and highlight the brain as the primary tool of the programmer (and all knowledge workers).

Conclusions

We've assumed the manufacturing metaphor through the Agile movement, but have we examined it? I believe the way we build software under the Agile umbrella is missing out on some of the best parts of modern factory work. If you look at it incorrectly, programmers are reduced to factory workers, trudging through their mindless work. Measurements of story velocity only incentivize the company to push for more features faster.

But we could be so much more! If you look at it from a different angle, programmers could be aligned with the business value and measured on its delivery instead of delivery of features that may or may not help the customer.

I hope exploring different ways of seeing our work can give us ideas for the ruts we're stuck in. In my experience, there is a lot of room for improvement. We're stuck thinking of ourselves as car assemblers when we could be designing cars--or even designing car manufacturing itself. And with these four metaphors, I wonder if there are more practices we can borrow from manufacturing.